Strategies - Promoting learning

- Introduction

- Providing tasks / activities well matched to the young person's ability level

- Building tasks around the young person's interests and skills

- Praising the young person

- Providing tangible rewards

- Providing numerous short periods of work

- Providing "space" between educational activities

- Enabling the young person to participate in the classroom with his / her peers

- Placing the young person appropriately in the classroom

- Preparing the young person to participate in educational activities

- Enhancing the young person's engagement in educational activities

- Providing a wide range of tasks to practise any given skill

- Breaking down tasks into small steps

- Using "jigsawing" to promote learning

- Avoiding triggers in lessons / educational activities

- Monitoring the young person for signs of stress / anxiety

- Re-directing the young person to the task

- Having additional tasks / activities ready

- Providing extra time to complete tasks

- Description of the TEACCH "structured teaching" approach

- TEACCH description - Physical structure

- TEACCH description - Schedules / timetables

- TEACCH description - Work systems

- TEACCH description - Task structure

- Providing zoning

- Providing a constant classroom layout

- Providing a work station

- Providing a carpet tile to indicate to the young person where to sit

- Providing a schedule / timetable

- Providing a work system

- Providing a finished box

- Minimising clutter

- Providing CCTV

- Regarding the long cane as part of the task structure during mobility lessons

Introduction

Generalising learning

Young people with visual impairment and autism have difficulty generalising what they learn. This means that an individual may

Practitioners should begin to work towards the generalisation of all learning from an early stage.

The difficulties associated with providing additional support

The young people featured in the case studies in this guidance material all have additional support. However, this is not always in their best long-term interests. It can be counter productive in relation to learning, to independence and to developing social relationships with peers.

Practitioners should therefore put in place measures to gradually reduce the amount of support.

Given Ali's age (he is only 4), the complexity of his difficulties and his sociability, he is regarded as needing the stability and security afforded by having additional support, from a designated teaching assistant (TA) for most of the school day. The school is aware that as Ali settles and matures, it will be important to decrease the involvement of his designated TA and to increase the number of other staff members who work with him. This should ensure he does not become emotionally over-reliant on one member of staff and will also support

Jasper has full-time teaching assistant (TA) support, but this is shared by 3 TAs. Staffing is thus arranged to encourage the generalisation of learning across staff members. The TAs communicate effectively with each other to promote consistency amongst team members.

Providing tasks / activities well matched to the young person's ability level

Some young people with visual impairment and autism have high standards for themselves and do not cope well with failing. They are therefore reluctant to engage in an activity if they believe they will fail. Young people need to be confident that they will succeed. This means that activities must be well-matched to the young person's ability level.

Dominic needs to feel that activities are within his range of skills; he needs to feel "safe" with them. This is because his self-esteem is rather low, he lacks confidence and he cannot easily cope with failure. Indeed, he sometimes thinks he has failed when, in fact, he has completed a task successfully. Staff therefore try to ensure that all the activities they provide for him are well matched to his ability level. This is particularly important when Dominic is stressed or anxious. Staff also ensure he is praised for hard work. "Safe" activities are those that are non-threatening for Dominic and which do not provoke anxiety.

A further issue is that some young people with visual impairment and autism are single-channelled and cannot attend to another person whilst engaged with a task.

This is the case with Sebastian. Staff understand that it is not appropriate to initiate communication with him when he is engaged in a task. This means that they know they cannot assist him with a task he finds difficult. Thus, staff have no option other than to wait for Sebastian to complete the task before speaking to him. It is particularly important to provide activities that are well-matched to Sebastian's ability level; if this is not done, there is a real risk that he will experience failure.

The same applies to Bob. Even if it is clear that he is struggling with a task, it is important that the member of staff supporting him says nothing, unless he requests help. If he struggles but fails to request help, it is important for the member of staff to monitor Bob's behaviour to judge his level of stress. Clearly, if his stress level rises, the practitioner needs to respond in order to reduce it again. So, as with Sebastian, it is particularly important to provide activities that are well-matched to Bob's ability level.

Providing activities that are well-matched to the young person's ability level is necessary, but not sufficient: it is also essential to make it clear to the young person that he / she has succeeded. Thus, praising the young person and / or providing a tangible reward is crucial.

Building tasks around the young person's interests and skills

All young people learn most effectively when they find tasks meaningful and motivating. This is particularly important for young people with visual impairment and autism. Indeed, if an individual is not interested or motivated, it may be impossible for practitioners to engage him / her in educational tasks.

An important factor for practitioners to bear in mind is that young people with visual impairment and autism are not concerned to engage in activities in order to please someone else. In addition, they are not necessarily motivated by the same things as their typically developing peers. Therefore, practitioners often need to take advantage of what motivates the individual, and build tasks and activities around his / her interests and skills.

Some young people with visual impairment and autism do not have identifiable interests and skills that can be readily used for building tasks and activities. For these individuals it will be particularly important to find an effective way to reward engagement, either with praise or with tangible rewards.

Archie is interested in vehicles, particularly heavy goods vehicles (HGVs). This interest is used to build maths tasks for him. For example, he enjoys calculations based on loads an HGV can carry or distances travelled.

Tyler is fascinated by regular patterns in the environment. Whenever possible, therefore, his teacher builds tasks and activities around this interest and skill. For example, he motivates Tyler and extends his number skills with the use of a braille number square.

When Jasper had the infection which caused his sight loss, he was absent from school for 5 months. On returning to school, practitioners ensured his curriculum centred on activities and materials he had liked prior to his absence; there was an emphasis on sensory experiences.

Praising the young person

It is, of course, important to reward engagement and learning. It is particularly important for those young people who do not have identifiable interests and skills that can be readily used for building tasks. For these young people it is essential to find an effective way to reward engagement, either with praise or with tangible rewards.

However, because young people with visual impairment and autism have difficulty with social understanding, many do not understand or respond well to praise. They are not concerned to please other people, so are not motivated when someone else is pleased with them and praises them. Indeed, some of these young people find praise aversive or confusing. Some become overloaded if verbal praise is lavished on them using a loud voice, especially if it is accompanied by clapping or physical contact. It is therefore important that practitioners use intonation and facial expression with care.

However, it is essential to remember that Autism is a wide spectrum and that young people vary enormously. Some individuals with visual impairment and autism do respond positively to praise, but care is required when using it.

Tyler is one such young person. Staff have therefore used praise in the past to motivate and encourage him. However, Tyler does not like other people to speak loudly, perhaps because he finds this over-stimulating. Thus, when they praised Tyler, staff said "Good boy" without raising their voices. However, although praise helped to motivate Tyler, its use gave rise to a difficulty: Tyler almost constantly sought praise and repeatedly asked his teacher "Am I a good boy?" A different form of verbal reward is now being tried: staff say "Good work." In fact, this is essentially the approach taken in the TEACCH "structured teaching" approach; practitioners using this approach typically say "Good job." In a way, therefore, it is the good work that is the focus, rather than the young person. Practitioners working with Tyler believe this approach is preferable to actually praising him, as he now less frequently seeks a reward.

In place of "Good work" it is often helpful to say saying something more specific like "Good sorting", "Good sitting" or "Good - hands in lap". This general approach to praising removes the focus from the young person, which is often helpful. In addition, it serves to remind the young person of the skill or behaviour being promoted at that time. In other words, it serves to remind the individual of what he / she should be doing.

Dominic also responds well to praise; this is noted in the Student Profile provided by his school's visual impairment resource base. However, it is important to speak quietly to him; again, this is noted in his profile. This is important, as he associates increased loudness with the speaker being angry and Dominic thinks he is being reprimanded. See also using intonation and facial expression with care. Praising Dominic quietly has the advantage of not drawing additional attention to him. As he is educated in a mainstream school, staff try not to make him stand out from his peers, as this could lead to teasing, or even bullying.

If the young person responds well to being praised for engagement and learning, it may also be appropriate to praise him / her for positive behaviour.

Providing tangible rewards

It is, of course, important to reward engagement and learning. It is particularly important for those young people who do not have identifiable interests and skills that can be readily used for building tasks. For these young people it is essential to find an effective way to reward engagement, either with praise or with tangible rewards.

Praise has been found to be ineffective with Sebastian. In contrast, some tangible rewards are effective. Sebastian has a deep interest in some toys and in cassette recorders, and this is used to provide him with tangible rewards: he earns a token for engaging in and completing every educational task and then exchanges these tokens for "reward time" which occurs during the last 10 minutes of the school morning and the last 20 minutes of the school afternoon. Sebastian receives "reward time" if he has earned a token for every task during the morning / afternoon. During "reward time" he is given access to a cassette recorder and the toys he is deeply interested in. Sebastian does not have access to these items at other times. His interest in cassette recorders is associated with his interest and skills in music.

Before the use of these items was restricted to "reward time", Sebastian was sometimes reluctant to finish playing with the toys and cassette recorder. However, both periods of "reward time" are followed by events Sebastian finds motivating: dinner and home time respectively. Thus, he almost always stops playing immediately at the end of "reward time".

The staff who work with Sebastian are very conscious of the need to ensure that they enable Sebastian to earn the tokens and therefore have "reward time." Thus, tasks are very carefully selected and structured to ensure that he will engage in and complete them. If, during a task, it becomes clear to a member of staff that Sebastian is not engaging, the task is modified to ensure he succeeds.

Thus, even when it is not possible to build tasks around the young person's interests and skills, it may be possible to use those interests and skills to provide tangible rewards for engaging in educational activities.

Tangible rewards can also be useful in promoting positive behaviour.

Providing numerous short periods of work

Dominic has a lot of energy, with a degree of hyperactivity / impulsivity and sometimes becomes restless in lessons which he does not find very motivating. To support his learning, he is provided with numerous short tasks, rather than fewer lengthy ones. However, if Dominic is using a computer, he can attend for a whole lesson (45 minutes) without losing focus.

Winnie and Tyler also learn most effectively with many short periods of work rather than fewer, longer sessions. Winnie attends for no more than about 5 minutes at most, though Tyler can attend for up to about 15 minutes. They are also provided with "space" between educational activities.

Educational tasks are presented to Amanda in numerous short periods. The number of tasks presented to Amanda on any occasion depends on her mood, as does the length of those tasks. Initially, Amanda was only able to work for periods of a few minutes. This has been built up so she now sometimes works for a period of 45 minutes, provided she is relaxed, calm and motivated.

Amanda is also provided with "space" between educational activities: see the next strategy.

Providing "space" between educational activities

In the spaces between her numerous short periods of work, Winnie is provided with "space" - periods in which she either has her favourite activity (listening to music) or goes for a walk. Walking is a sensory integration activity recommended for Winnie by the occupational therapist.

Tyler has "space" between his numerous short periods of work. In these periods he is able to relax, or take exercise.

Stacey has "independent time" between educational activities to provide her with "space". However, during these periods, she is unable to remain at any activity for more than about two minutes, after which she engages instead in rocking. Because these periods are unstructured, Stacey does not understand what she should do, and lacks the ability to select a functional activity for herself. This is a common difficulty for young people with visual impairment and autism. Consideration is now being given to making the periods between educational activities more supportive for Stacey. Stacey has a high level of energy and presents as restless. She also requires a good deal of sensory input. Therefore, it is likely she will have opportunities for physical exercise and opportunities to use her Eggcersiser, enabling her to fulfil a sensory need appropriately.

Amanda is provided with numerous short periods of work. Between these periods, the practitioner offers her a choice of two sensory activities by presenting her with two pictorial symbols and asking "Which one?". The activities offered depend on Amanda's arousal level and emotional status and include

In making her selection, Amanda points to the symbol representing her preferred activity.

Enabling the young person to participate in the classroom with his / her peers

Amanda has very high levels of anxiety at times. When she was admitted to her current school a few years ago, she was highly anxious and was unable to function in a classroom environment. This resulted from negative experiences in previous schools from which Amanda was excluded. A programme was put in place to enable Amanda to participate in her classroom with her peers.

Amanda first worked individually with a member of staff in a resource room with no other young people present. This room was located a considerable distance from her classroom. Gradually, Amanda's work-place was moved towards her classroom. This took place over a period of a few weeks. At the end of this period, Amanda presented as calm, and she was invited into her classroom. This was successful: Amanda is now able to sit and work in a busy classroom setting, although she still requires individual support.

In contrast, Bob is not expected to participate in his classroom with his peers. As described in providing a low arousal environment, Bob's sensory difficulties are such that it is inappropriate to require him to do so.

When Jasper had the infection which caused his sight loss, he was absent from school for 5 months. On his return to school, provision was tailored to address his needs. One aspect of this was concerned with enabling him to participate in his classroom with his peers. A room was set aside for his sole use where he was supported by one member of staff. It was decided at this stage that it was important to ensure that Jasper did not come to rely on only one member of staff. However, it was also recognised that a lot of change was inappropriate, so two members of staff shared Jasper's support, alternating from day to day. He now works in the classroom with his peers, whom he tolerates well.

Placing the young person appropriately in the classroom

Dominic sits at the front in lessons. This is partly to address his poor sight: he can see the teacher more clearly and any materials or visual supports the teacher uses, such as those displayed on the interactive whiteboards. Placing Dominic at the front of the class also reduces visual distractions caused by his peers; it reduces the risk that he will become distracted by the clothes, hair or movements of the other young people. If Dominic sat further back in the room, his environment would be more stimulating visually, and there would be a risk of him becoming overloaded.

It is important to note that other young people with visual impairment and autism might find it less distracting to sit at the back of the class. Being placed at the back would enable the individual to view the whole room and everyone in it. This would obviate the need to turn round to find out what is going on. Another factor to consider in this regard is that some young people with visual impairment and autism appear to find it unsettling and worrying to have other people behind them; it seems to make them more anxious. Thus, some young people may need to sit at the front of the class because of their poor vision, but to sit at the back because of their need to see the whole room. It will be necessary to judge how best to manage this on an individual basis.

Preparing the young person to participate in educational activities

When Ali is presented with a task, he quite often fails to engage with it initially. On these occasions, staff prepare him to engage by providing him with his electric toothbrush; he uses this for a minute or two and then focuses on the activity.

Before Jivan is asked to sit on a chair to participate in an educational activity, he uses a physiotherapy ball for about two minutes. This has been recommended by the occupational therapist in order to increase the length of time he sits on a chair. The teaching assistant supports Jivan to lie over the ball which she then rolls gently, encouraging Jivan to balance himself and stay on the ball. This prepares Jivan to sit on his chair to and thus prepares him to participate in educational activities.

Archie really enjoys listening to music and often sings along, but has no special musical abilities. He is particularly interested in musicals. "Hairspray" is his current favourite and he will do a lot for a member of staff who sings "Motion of the ocean". Archie seems to view the singer of the song more favourably; he appears to believe that the two of them have a common interest, and he seems to be more willing to work for the person. Thus, if Archie is reluctant to participate in an educational activity, singing "Motion of the ocean" is used to prepare him to participate. This almost always results in Archie taking part. If he loses interest during the activity, this strategy is also used to enhance his engagement.

Winnie learns most effectively with numerous short periods of work rather than fewer, longer sessions; she attends for no more than 5 minutes at most. However, it is difficult to predict how much work Winnie will cope with as this is dependent on several factors; those that have been identified are

Winnie usually works best during the first half of the morning and again during the first 45 minutes of the afternoon; it is thought this is because she is not hungry at these times, and her peers tend to be quieter. Even when she appears to be ready to participate in an educational activity, Winnie does not always readily engage. Naturally, she is more likely to engage if the activity is intrinsically meaningful or interesting to her, but this is not always possible. On these occasions, the teaching assistant (TA) prepares her to participate by quietly singing to her. This strategy was first tried because it was clear that Winnie enjoys music and finds singing calming. Initially, the TA quietly sang familiar nursery rhymes to Winnie. Nursery rhymes are no longer considered to be age-appropriate (Winnie is nearly 12). Therefore, the TA is now using a mixture of nursery rhymes and current pop songs. As yet, the pop songs are not as effective as the nursery rhymes; the TA hopes this will improve as Winnie becomes more familiar with their use. As noted above, Winnie attends for no more than 5 minutes at most. If she loses interest early on in an activity, the TA also employs the singing strategy to enhance her engagement.

Amanda is commonly quite tired and lethargic in the morning and therefore uses a peanut ball in order to help wake her up and prepare her to participate in educational activities. She bounces on the ball for about 5 minutes. While she does this, a member of staff gives her choices of songs to sing and encourages her to join in by singing missing words. The peanut ball is also used at times to enhance her engagement in educational activities.

Amanda also uses a Thera-Band to prepare her for sitting down and working for up to an hour; she stretches with the Thera-Band and a member of staff supports her to make big body movements.

The sensory activities listed here have been recommended by the occupational therapist (OT). Practitioners are strongly advised to obtain the advice of an OT before using items such as Thera-Bands and peanut balls.

Enhancing the young person's engagement in educational activities

During educational activities, Jivan sits on a Move "n' sit Air Cushion which is placed on his chair. Staff believe the cushion enables him to sit for longer than would otherwise be the case; they believe it enhances his engagement in educational activities.

When she first attended school, Stacey often sat in a slouched position, swung on her chair or rocked. The occupational therapist believed Stacey's poor sitting posture indicated a need for increased vestibular and proprioceptive input, to help her increase her postural security and therefore give better internal awareness of where she is in her immediate surroundings. The occupational therapist therefore gave advice about improving sitting posture : Stacey now has an inflatable wedge Cushion designed to improve sensory input. This cushion has made a significant difference to Stacey's sitting posture. In addition, because she is now more stable and secure, Stacey can give more of her attention to educational activities. Thus it enhances her engagement in educational activities: she now engages more effectively and attends for longer. In turn, this means she is now learning more effectively.

Winnie attends to educational activities for no more than 5 minutes at most. If she loses interest early on in an activity, the teaching assistant (TA) quietly sings to her to enhance her engagement. The TA also employs this strategy sometimes to prepare her to participate in educational activities and to calm her.

If Archie is not attending well to an educational activity, his engagement can often be enhanced by using the strategy sometimes used to prepare him to participate in educational activities.

Jasper wears a weighted vest during educational activities to enhance his engagement. This is one of several sensory integration activities recommended by the occupational therapist.

Amanda is sometimes provided with a peanut ball to enhance her engagement in educational activities: she carries out tasks (e.g. completing puzzles) whilst leaning over the ball. Doing this helps Amanda to regulate her arousal level when she is feeling stressed or over-aroused.

The use of a peanut ball has been recommended by the occupational therapist (OT). Practitioners are strongly advised to obtain the advice of an OT before using this item.

Amanda also uses a peanut ball to prepare her to participate in educational activities.

Providing a wide range of tasks to practise any given skill

Some young people with visual impairment and autism do not readily repeat activities or experiences they have already engaged with; they seem to adopt the attitude of "I've been there, done that, got the T-shirt".

Young people need to practise skills many times before they can accomplish them competently, so practitioners need to be inventive.

Sebastian is reluctant to repeat tasks, so his teacher tries to present tasks in novel ways to ensure he engages - e.g. by practising spellings in a variety of ways, such as in braille, on tape and verbally.

Breaking down tasks into small steps

Breaking down tasks into small steps is a strategy commonly used to enable young people with learning difficulties to learn more effectively. It can also support young people with visual impairment and autism.

For example, Cecily finds dressing and undressing (for PE lessons) difficult. These tasks are broken down into small steps for her.

Using "jigsawing" to promote learning

"Jigsawing" is an approach in which a task has several components. Each component is given to a small group within the class or to an individual young person working within a small group. In this way the task can only be completed if everyone achieves their part. This requires the teacher to ensure that the separate components of the task are carefully chosen and that each young person is capable of achieving his / her task independently to avoid being viewed as the weak link within the group. Because everyone contributes to the task, all are valued when the result is achieved. Research suggests that if given free choice as to who should be chosen for group activities at a later date, less popular peers are now viewed more favourably.

For more information on jigsawing, see Howley and Rose (2003), Rose (1991 ) and Rose and Howley (2003).

Archie has a range of difficulties with social communication and peer interaction. Jigsawing is used to promote his peer relationships.

Avoiding triggers in lessons / educational activities

Tyler is deeply interested in vehicles and talks a great deal about this topic. In the past, he often used to talk about vehicles during lessons. In lessons, therefore, staff avoid the triggers of

He has now been given a clear boundary concerning this issue: "Work in lessons. Talk about vehicles at break." If he does talk about vehicles in a lesson, he is redirected to the task. He is also praised when he is attending to the task by being told "You're working well. That's good." Tyler now rarely talks about vehicles during lessons.

The mobility officer has found it is very easy to trigger Tyler into talking about vehicles when out in the community. As far as possible, therefore, she avoids the trigger of referring to vehicles. Indeed, she understands that it is not appropriate to initiate communication with Tyler, unless she needs to do so in relation to his mobility task.

Avoiding triggers is also discussed in relation to promoting positive behaviour.

Monitoring the young person for signs of stress / anxiety

It is important to constantly monitor the behaviour and moods of a young person with visual impairment and autism, including during educational activities.

This is because some young people become stressed / anxious during educational activities. If a practitioner becomes aware that a young person is becoming stressed / anxious during an educational activity, he / she should take steps to reduce that stress / anxiety. If the individual's stress / anxiety is not reduced, the young person fail to learn; in addition, he / she will come to find educational activities aversive. There is also the risk, of course, that the stress / anxiety will escalate, causing the young person to reach crisis or overload.

Winnie becomes stressed / anxious during an educational activity if it lasts too long. She attends for no more than 5 minutes at most. However, it is difficult to predict how much work Winnie will cope with as this is dependent on several factors; those that have been identified are

It is particularly important that the teaching assistant (TA) supporting Winnie during an educational activity monitors her for signs of stress / anxiety. If the TA believes Winnie is becoming stressed / anxious because the activity is lasting too long, she brings the activity to a close.

Amanda has a team approach and now receives full-time individual support. Initially, there were times when Amanda was expected to work independently. However, it became clear that this was not appropriate. During educational activities, staff monitor Amanda (as they do at all times); their observations of her when she was given work to carry out independently indicated that she was unable to manage non-directed time in order to work independently. Amanda now receives constant individual support. This has contributed to promoting her positive behaviour and her emotional wellbeing, as well as her learning.

Redirecting the young person to the task

Some young people with visual impairment and autism become distracted from tasks and focus instead on something else. The cause may be an event that occurs which captures the individual's attention; it is often an area of deep interest to the young person.

The first of these reasons applies to Dominic, who becomes distracted at times in lessons when his (non-disabled) peers become disruptive. In these situations, the teaching assistant (TA) redirects him to the task set by the teacher. The TA also calms Dominic when he becomes anxious by redirecting him to the task.

Cecily is distracted at times from her educational tasks: she starts to talk about a favourite topic, currently certain television programmes and their associated music. When this occurs, the teaching assistant re-directs her to the task, telling her "Work now. Talk later." This is a variation of the "now / next" approach.

Tyler also becomes distracted from educational tasks: he talks about his favourite topic of vehicles. At these times, he is redirected to the task. He is also praised when he is attending to the task by being told "You're working well. That's good." Tyler has made progress in this respect: he now rarely talks about vehicles during lessons. See also avoiding triggers in lessons.

Amanda has a schedule. However, sometimes Amanda tries to rush through work in order to get to a preferred activity. This is particularly likely to happen if there is an after-school activity that Amanda is looking forward to. In these situations Amanda is redirected to her current task, using the "now / next" approach. For example, the practitioner tells her "now work; next music" or "now school; next club".

Occasionally, Amanda leaves the classroom to go to the location of the activity she desires. When this occurs, the member of staff working with Amanda follows her and repeats the "now / next" prompts until Amanda returns to the classroom. Sometimes it is helpful to redirect Amanda back to her visual schedule to help her understand that the desired activity is coming later.

Having additional tasks / activities ready

Many young people with visual impairment and autism cannot readily use "spare" or time unstructured constructively. When these individuals are not directed clearly to an activity of some kind, they are at a loss, perhaps engaging in habitual, self-stimulatory activities. At these times there is a risk that they become overloaded, making it difficult for them subsequently to engage in educational tasks. In addition, they may become distracting and irritating to both practitioners and peers.

Dominic is at a loss during unstructured times. The teaching assistant (TA) supporting him always has additional activities ready in case he completes the tasks set by the teacher before the end of the lesson. Without being provided with something to do, Dominic cannot select an activity for himself, and there is a risk that he will become disruptive. The TA also has spare paper and pencils for him in case he starts to lose focus as a result of becoming overloaded in some way. Drawing or writing down the ideas and thoughts that are in his head at the time enables him to calm down.

Providing extra time to complete tasks

Many young people with visual impairment and autism require additional time to complete tasks. It is not surprising that visual impairment slows young people down; autism does this too, in particular because it increases the time required to process information and to organise activity.

Tyler's need for additional time is marked. He is provided with extra time to complete tasks and to make transitions from one part of the school to another.

Providing extra time is also important in promoting mobility and independence.

Description of the TEACCH "structured teaching" approach

This section uses material provided by Iain Chatwin1 and by Kim Taylor2 and David Preece3. Their help is gratefully acknowledged.

1 Staff Training Advisor, Sunfield*

2 MSI Teacher, Greenfields School, Northampton*

3 Team Manager, Services for Children with autism, Northamptonshire Children and Families Service*

* Correct at the time of writing the first version of this guidance material in the spring of 2011.

The Project Team remains responsible for the content.

The TEACCH "structured teaching" approach was developed at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill in the 1970s by Eric Schopler and is now used worldwide. TEACCH stands for Treatment and Education of Autistic and other Communication-handicapped Children and Adults. It is probably the most widely used teaching approach employed with autistic young people and adults.

As it is very adaptable, TEACCH can be used to support and teach people with a very wide variety of individual needs and abilities. TEACCH is used successfully with people with all kinds and degrees of learning difficulty as well as sensory difficulties. Individualised TEACCH programmes are used in a variety of settings. They support autistic people to be more independent, to access social activities, to carry out tasks in the work-place and develop leisure interests. The more the approach is adapted to meet an individual's needs the greater its success.

For information about the use of structured teaching with young people who have visual impairment, see Howley and Preece (2003) and Taylor and Preece (2010).

TEACCH is based upon the concept of the 'culture of autism' - that people on the spectrum share a common way of perceiving and experiencing the world. The approach acknowledges the core difficulties of autism:

TEACCH attempts to compensate for these difficulties. Most autistic people are considered to learn most effectively using vision. For fully sighted people, TEACCH therefore uses the person's visual strengths. For a young person with no useful vision at all, the approach will have to be adapted to use another sense. For a learner with some useful vision, it may be most appropriate to use this, whilst compensating for his / her individual difficulties; this might require, for example, magnification and enhancing contrast.

TEACCH also capitalises on other common characteristics of autistic people

In effect, TEACCH provides a system for organising the learning environment, developing appropriate activities and helping the young person to understand what is expected of him / her.

A priority within the TEAACH approach is to build on emerging skill areas rather than focusing on areas of skill deficit. Assessment of the individual is central to the approach. It is important to identify the young person's interests, limitations, sensitivities and emerging skills.

The environment, tasks and supports are individualised for each young person to maximise his / her learning, motivation and independence.

The TEAACH approach has four basic components each of which is an essential part of the whole approach:

i. physical structure

ii. schedules

iii. work systems and

iv. task structure.

It is important to provide some words of caution here. Some aspects of TEACCH are not easy to understand initially, and cannot be explained easily. Those who are interested in adopting the approach are advised to undertake specific training in TEACCH.

There is no set TEACCH curriculum. Instead, those using the approach capitalise on each individual's strengths and interests in order to cultivate engagement. It is essential to build on what the young person has to offer, to develop motivation and to focus on functional skills.

TEACCH description - Physical structure

Physical structure is used to organise the environment so that it makes sense to the autistic person. Adapting the environment to create clearly defined areas (or zones) helps the individual to understand where activities take place. Physical structure includes

Zoning also helps the learner to understand the nature of the current task, because, for example, one-to-one work always takes place in the same zone, and independent work in the work station.

Sometimes it is not possible to provide a zone for each activity that takes place in the classroom. However, changing the physical structure of a situation can be effective. For example, placemats can indicate that the classroom table is to be used for snack; a waterproof covering that it is to be used for painting; an old curtain that it is to be used for craft.

Zones should be clearly defined so that young people understand the boundaries between them. For those with visual impairment and autism, zoning can support navigation around the classroom.

TEACCH description - Schedules / timetables

There is the scope for some confusion over terminology when discussing schedules / timetables. "Schedule" is the term usually used by those who employ the TEACCH approach. However, many practitioners in the UK provide young people with "timetables". In effect, the terms "schedule" and "timetable" are interchangeable. The choice of term is not important except that whichever term is adopted, it must be used consistently; switching between "schedule" and "timetable" is likely to confuse the individual, and, indeed, may confuse practitioners. In this description, "schedule" will be used. However, when describing strategies, "timetable" is used if that is the term employed with the young person in question.

Many young people with visual impairment and autism have difficulty understanding the expectations of others which can lead to anxiety and stress. Transitions from one activity to another can be particularly difficult. Poor sequential memory and time organisation skills are also common amongst autistic individuals.

While physical structure enables the young person to understand where activities will take place, the schedule is (typically, for sighted autistic learners) a visual cue, or series of cues, that tells the individual what activities will occur and in what sequence. It enables the young person to predict what will happen next.

Using a schedule can build flexibility; though events change, the routine of checking the schedule remains constant. This can ease transitions and promote independence.

Schedules vary widely depending on the young person's abilities and needs. The communicative means used in a young person's schedule must be selected to meet that individual's needs and preferences. It is not necessary for schedules to be visual: for example, a young person with visual impairment and autism who has limited skills can use a schedule which employs functional objects; a learner who is more sophisticated can use a schedule which employs a tactile alternative to print.

Schedules can vary in length; the simplest specifies only what is happening next; in contrast, it is possible to provide a schedule showing all the activities that will take place during the day. It is fundamentally important that the schedule is

Many young people with visual impairment and autism have difficulty engaging in activities they dislike, find aversive or expect to fail at. This can be addressed by alternating such activities with those the individual finds motivating. The schedule can support this by clearly showing the young person what comes next.

Additional information on schedules / timetables is available in the article on structured teaching at teacch.com/educational-approaches/structured-teaching-teacch-staff. (Accessed 18th December 2014.)

TEACCH description - Work systems

While the schedule enables the young person to understand what activity comes next, the work system gives the individual a systematic way to approach the tasks within that activity; it shows what work needs to be completed. Once the young person has learned how to use it, the work system enables him / her to work independently. It also informs the learner of what he / she needs to do, how much work to do, when the task is finished, and what comes next.

As with schedules, the work system should be individualised for each young person. At the most basic level it is practitioner directed: the practitioner gives the individual the work, and removes it when the task is finished. At a more complex level, the young person works independently, from left to right or top to bottom. For example, the individual may take a task from a shelf on his / her left, and put the completed task in a finished box on his / her right. To know what to do next the young person may match shapes, letters or numbers provided in sequence on the work table with identical markers attached to the task. For a learner with very little or no sight, these markers can have strong tactile features. A learner who can read print may work from a printed list; a learner who uses Moon or braille, can use a schedule in the appropriate tactile medium.

Crucially, the work system, and the tasks, must be sufficiently motivating and interesting to the young person, and should be of practical value.

TEACCH description - Task structure

While the work system shows the young person what tasks they will so, task structure shows them how to undertake and complete the individual tasks.

Because young people with visual impairment and autism have difficulties with social interaction and processing language, they also have difficulties responding to verbal instructions. Task structure minimises these difficulties, capitalising on their visual strengths by presenting instructions and organising the task visually (for most sighted autistic learners).

For the young person with little or no sight, vision may need to be replaced, perhaps using touch.

Some young people with visual impairment and autism may be able to use auditory cues or even a brief recorded message provided by a voice output communication aid (VOCA). It is also possible to use such devices to label rooms, and to label items in classrooms and cloakrooms.

For a young person with visual impairment and autism, a major drawback with spoken instructions is that they are lost as soon as they have been given; see also the need to augment spoken language. In contrast, the individual can independently refer to a visual or tactile instruction or use a VOCA as many times as necessary without having to ask, a powerful factor in reducing his / her anxiety.

However, some young people with visual impairment and autism might become deeply interested in VOCAs, and may return to them repeatedly to hear the messages over and over again.

Some VOCAs permit a new message to be recorded, deleting the previous one; a young person may discover this and render the devices ineffective. VOCAs clearly need to be used with caution.

Visual (or tactile) structure can also support the young person to stay on task. For example, during a mobility lesson, the individual's long cane itself is a constant reminder of what the task is, and can therefore be considered to be an aspect of task structure. In fact, the long cane can also be viewed as an object of reference for "mobility training".

Providing zoning

Zoning, an aspect of physical structure, is used to some extent in Sebastian's class. For example, the soft chair corner is always used when the teacher addresses the whole class; the young people always undertake formal educational activities at the tables placed in the centre of the room. Each learner has his / her own place at these tables.

Tyler's classroom is divided more clearly into several zones

Providing a constant classroom layout

This aspect of physical structure helps to promote independence. Cecily, Jasper, Sebastian and Tyler are all provided with a constant classroom layout. This is discussed in greater detail in providing a classroom layout that remains constant.

Providing a work station

For some young people, a crucial aspect of physical structure is the work station. The work station is intended to reduce the sensory information available to the learner by minimising distractions. This enables the young person to concentrate on the task. A work station often consists of a table pushed against the wall, with screens at the side; for a very distractible learner, it may also be appropriate to provide a screen at the back which can be moved to allow the learner and a teaching assistant to get into / out of the work station. A work station may also have a shelf to the young person's left and another to the right to accommodate the work system.

As the purpose of the work station is to sensory stimulation, it is important to ensure that clutter is minimised: the wall in front of the young person and any screens employed should be kept clear of pictures or other potentially distracting items.

Several of the young people featured in the case studies in this guidance material are provided with work stations, including Bob, Jasper and Stacey.

Jasper's work station is important for him as he becomes angry and cannot focus on a learning activity when several people are close by. His work station is in a corner of the room.

Bob is usually unable to access the classroom with his peers and is usually taught in a separate room. During the course of the week, he uses a range of rooms. Each one has a work station set aside for him. The precise nature of the work stations varies from room to room. However, there are some common features.

All Bob's work-stations are located near the room's entrance door. This enables him to leave the room quickly and easily should he go into crisis / overload.

Each work-station consists of a table pushed up against the wall. No items are stored on the table top. Bob faces the wall when he uses a work-station. Clutter is minimised: the walls he faces are blank, being kept free of notices, pictures and all other display items. Although Bob usually works in a different room from his peers, he nevertheless attends more easily to educational activities when using a work station; if he uses a table in the centre of the room, he is more readily distracted visually by the furniture and items stored on cupboard tops and open shelves. In particular, if the activity he is engaged in does not involve the use of a computer, and Bob can see one in the room, he is unable to attend to his task. However, facing the wall at his work station, he is not distracted.

Initially, Stacey found it difficult to focus on learning activities in the classroom, becoming very distracted when peers passed close by. The movement of the other young people near-by made her anxious, as she could not understand why her peers were out of their seats, or where they were going. Members of Stacey's staff team thought she believed that everyone else was leaving the room. This apparently resulted in her becoming very stressed, as she had not been told to go anywhere. To enable Stacey to focus more easily, she now works alone at a table, away from her peers. In effect, this table acts as a work station for Stacey.

Providing a carpet tile to indicate to the young person where to sit

Stacey has a carpet square, which can be viewed as an aspect of the physical structure component of the TEACCH approach. She sits on the carpet square during circle time, when the young people all sit on the floor.

Before being provided with the carpet square, Stacey did not understand whereabouts on the floor to sit; she fidgeted a great deal and moved around the floor. Thus, she was unable to attend to circle time activities. Now she knows that she is required to sit on the carpet square, she sits still and remains in one place. Consequently, Stacey is now fully included in the class group and attends when resources are passed around the circle or when songs are sung.

Jivan is also provided with a carpet tile to inform him of where he should sit during 'floor time'.

Providing a schedule / timetable

Providing a schedule / timetable has close links with supporting receptive communication as, in effect, it is an additional way to augment spoken language. This is because the schedule / timetable is designed to communicate to the young person what is happening, and in what sequence. However, schedules / timetables are described here as they are an essential component of the TEAACH approach.

A wide range of communicative means is available for use in schedules / timetables. They are

Selecting the means of communication to be employed in a young person's schedule / timetable should be part of the wider process of selecting the means of augmenting spoken language.

Archie has a timetable which uses tactile versions of abstract symbols. These are based on the standard range of Widgit symbols (now superseded by the Communication in Print programme) used by his peers.

Archie's tactile symbols are slightly larger than the standard visual symbols; they are approx 5cms square. Although the tactile symbols are very similar to the visual ones on which they are based, they are simplified. Thus, whereas the visual symbol for "dinner" shows a plate with food on it, with a knife to the right and a fork to the left, Archie's tactile symbol just has a circle with a line each side for the cutlery.

The symbols are made using Zy-Tex Paper and a Zy-Fuse Heater. The symbols were originally larger than those Archie now uses; they have been reduced in size as his understanding of them has developed. However, he still only has a fairly limited repertoire of tactile symbols. This is because, as his brailling skills improved, it was decided to focus on braille rather than extend the range of tactile symbols. A factor taken into consideration was the belief that some of the possible additional symbols would be too abstract for him. In addition to the tactile symbols, Archie now has an expanding range of pieces of braille paper each with a word in braille on it. In the course of time, if he makes sufficient progress learning braille, it is possible that the tactile symbols will be replaced with brailled words.

Archie's personal timetable is contained within a cardboard booklet (like an open folder). It is arranged top to bottom, with the tactile symbols and braille paper being attached using Velcro®. The timetable is portable and accompanies Archie when he leaves the classroom. Currently, a teaching assistant takes it, but the aim is that Archie will take it himself in due course.

Although his personal timetable is arranged top to bottom, his brailled version on the classroom wall is arranged left to right. Archie appears to have no difficulties using the two different arrangements.

When a timetabled event has finished while Archie is using his portable timetable, Archie removes the tactile symbol and inserts it in a flap at the back of the folder. This acts, in effect, as a finished box. When he is using the brailled timetable in class, he removes the relevant piece of braille paper and places it in the finished box at the end of the strip of Velcro®.

Archie's portable timetable covers four events. His classroom version covers either the full morning or the full afternoon, as appropriate.

Currently Archie still requires some verbal prompting to use his timetable. The aim is for him to be independent.

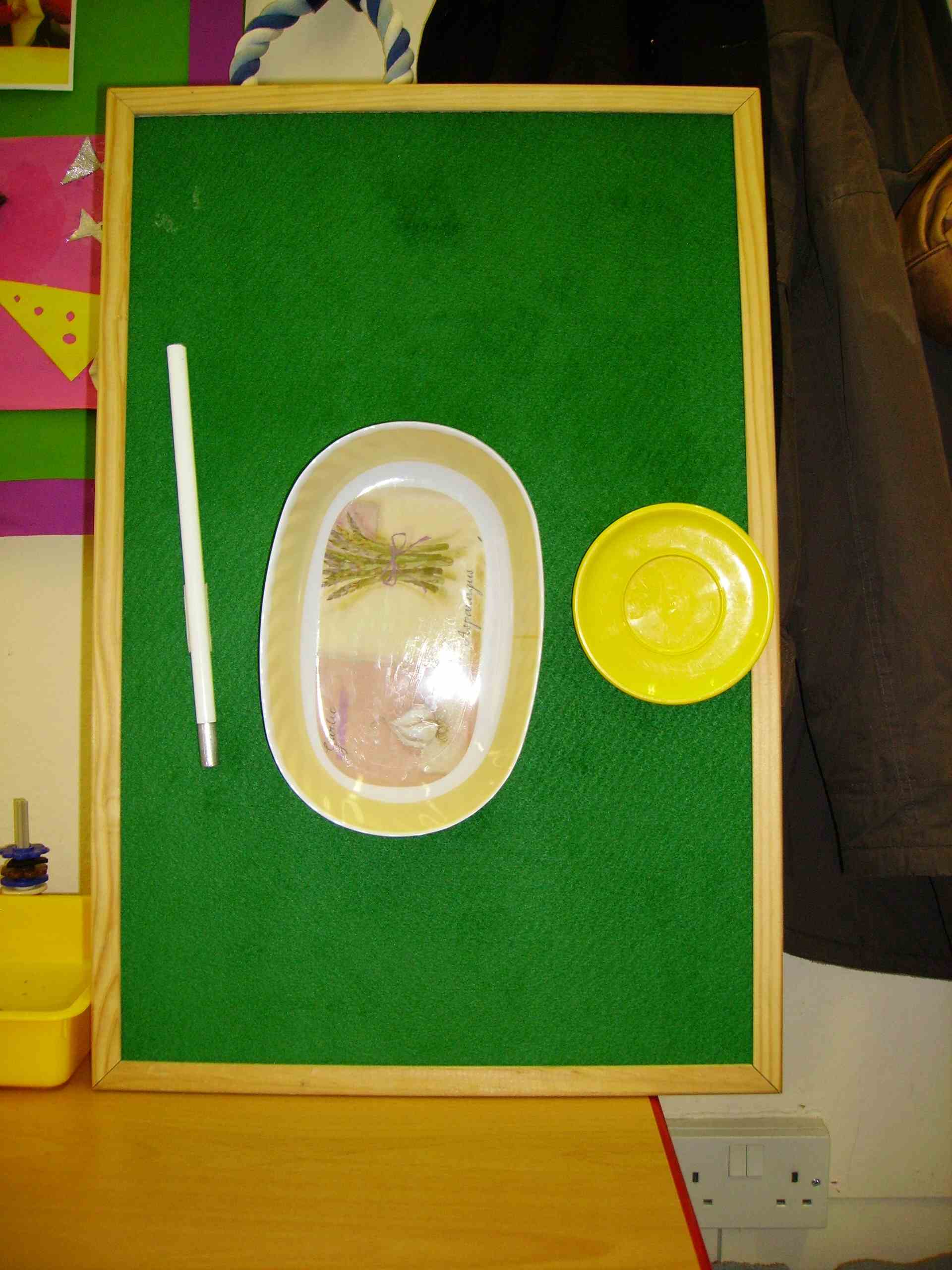

Sarah, who has no functional vision, uses an object timetable which covers part of the day. The timetable consists of a board approximately 50cm x 25cm, covered in felt. This is propped up on a table in Sarah's classroom where she can readily access it. Each activity is indicated either by an object identical to one she uses in the activity itself, or by an object of reference which stands for the activity. The objects are arranged left-to-right on the board in the same sequence as the activities themselves. They are attached to the board using Velcro®.

At present, Sarah is considered to have the ability to manage information concerning 3 or 4 activities, meaning a timetable for the whole day would be too complex for her. In addition, a whole day timetable would currently be impracticable, because it would not be possible to display all the objects.

The photographs below show Sarah's timetable for the first part of a school morning. The timetable for this part of the day is always set up before school by the member of staff who will be working with her.

In photograph 1, the timetable informs Sarah that she is to have mobility first, followed by an activity which promotes healthy eating, and then snack.

Once the morning greeting session is over, Sarah is guided to her timetable. The member of staff working with her says "Check timetable" and, using the hand-under-hand approach, guides her hand to the left side of the board, up the left hand edge about half-way, and then across.

Photograph 1

When Sarah encounters the first object (in this case a section of a long cane), the member of staff says "Mobility", and guides Sarah to remove it. Sarah then has her mobility session, which begins in the classroom. Her teacher, who provides the session hands Sarah her long cane, and takes from her the long cane section used on her timetable.

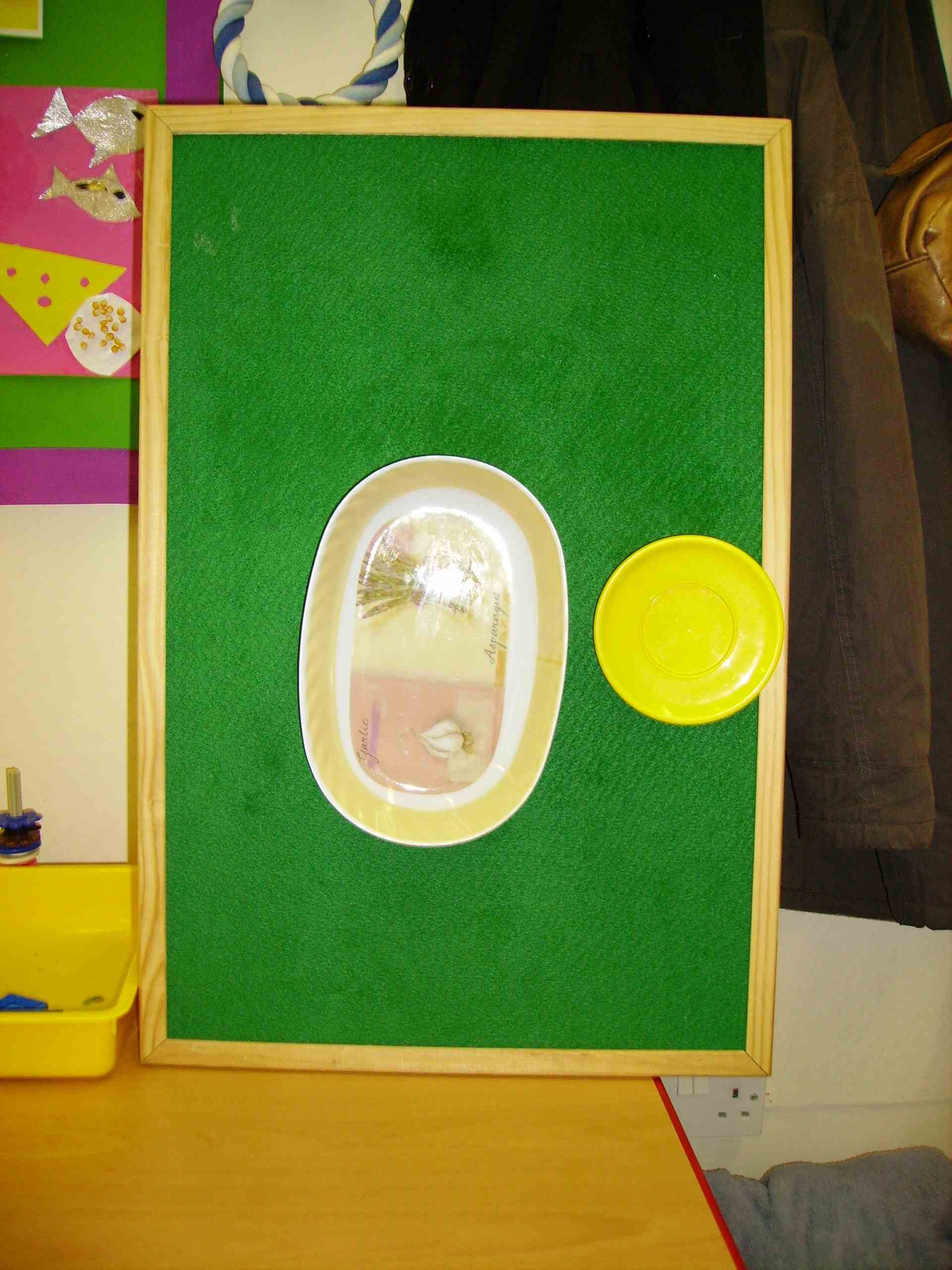

When mobility is over, the member of staff working with Sarah says "Finished"; she augments this with the on-body sign; Sarah is then guided to place her long cane in her finished box (photo 2), and, again, the member of staff says and signs "Finished".

Photograph 2

The member of staff working with her again says "Check timetable" and, using the hand-under-hand approach, guides her hand to the left side of the board, up the left hand edge about half-way, and then across. When Sarah encounters the first object (now a dish), the member of staff says "Healthy eating", and guides Sarah to remove it. Sarah then has her healthy eating session: holding the dish, she is guided to her table in the classroom; on reaching her chair at the table, Sarah is guided to sit down; she is then supported to place the dish on the table; it is then used in the healthy eating session.

Photograph 3

When the healthy eating session is over, the member of staff working with Sarah says "Finished"; she augments this with the on-body sign; Sarah is then guided to place the dish in the finished box, and, again, the member of staff says and signs "Finished". (Not illustrated.)

The member of staff working with her again says "Check timetable" and, using the hand-under-hand technique, guides her hand to the left side of the board, up the left hand edge about half-way, and then across. When Sarah encounters the first object (now a small plastic plate), the member of staff says "Snack", and guides Sarah to remove it. Sarah then has her snack: holding the plate, she is guided to her table in the classroom; on reaching her chair at the table, Sarah is guided to sit down; she is then supported to place the plate on the table; it is then used for her snack.

Photograph 4

When snack has finished, the member of staff working with Sarah says "Finished"; she augments this with the on-body sign; Sarah is then guided to place the small plastic plate in the finished box, and, again, the member of staff says and signs "Finished". (Not illustrated.)

During snack the member of staff working with Sarah for the second part of the morning sets up the timetable again.

Jasper has a schedule using objects of reference, arranged horizontally in a shoe tidy. No more than 3 activities are included at any one time. Currently, Jasper is prompted to refer to his schedule, but it is always displayed in the same place in the hope that, ultimately, this will enable him to locate it and refer to it independently. Some of the objects are used to support him during transitions around school.

Cecily is a braille user and has a brailled timetable. The timetable consists of an A4 size board in portrait format. It is covered with felt. This is used to display small pieces of braille paper, each with a piece of Velcro® on the reverse, and with a brailled description of a single timetabled activity. First thing every morning Cecily sets up her timetable for the day with support from a teaching assistant (TA). The TA and Cecily discuss the day's activities, going through them in chronological sequence. When a timetabled activity has been identified, Cecily finds the relevant label in the storage box and places it on the timetable board. She requires some support from the TA to place each label appropriately. They are arranged vertically. Having put her timetable together, Cecily locates the first label to remind herself of the first lesson. When that lesson is over, she returns to her timetable and removes the label, placing it on another A4 sized board, which acts, in effect, as a finished box. She then locates and reads the next label so she knows what is happening next. The process is repeated through the day.

A printed schedule is provided for Bob every day. A teaching assistant (TA) presents this to Bob in the first session every morning. Bob reads it; occasionally he asks the TA to clarify something on the schedule. Consideration was given to including Bob in the production of his schedule. However, it was decided this would be a lengthy process, likely to raise Bob's level of anxiety. Bob likes to read through the schedule as soon as possible, so he knows what he will be doing during the day.

Bob is also provided with a schedule for each lesson. These set out all the tasks he is to carry out in the lesson and provide instructions. In effect, each of these lesson schedules is a work system for the lesson. Bob always has the day's schedule and a pencil with him; as an event on the schedule is completed, he draws a line through it. Similarly, as soon as it is finished, he draws a line through each item on the lesson schedule.

Amanda needs to know her daily routine and frequently asks "What's coming?" when anxious or distressed. A schedule is therefore used to reduce her anxieties about what is to happen. This visual schedule is arranged vertically, covers the whole of the school day and is positioned near to her work station.

Pictorial symbols are positioned down the schedule (e.g. "work", "swimming", "pottery", "lunch", etc). The first three activities in the day are always the same, and in the same sequence: first toilet, then sensory work, then table top work. This helps Amanda to settle into the school day. Initially, Amanda required a symbol for each specific task (e.g. "counting", "reading" and "writing"). She now understands that these are all "work".

The schedule is set up before Amanda arrives each morning. This is the responsibility of the same member of staff every day. When Amanda first enters the classroom in the morning, the practitioner runs through the schedule with her. She points to each activity in turn, prompting Amanda to name it.

When Amanda completes each activity the practitioner prompts her to remove the symbol and place in her finished box.

Amanda also has a portable schedule, attached to the back of a folder. Typically, three visual symbols are used on this schedule to help Amanda understand the next few tasks.

Occasionally, Amanda removes the symbol representing an activity she does not want to do. The practitioner responds with humour, prompting Amanda to return the symbol to her schedule. This works well.

Young people sometimes experience difficulties using a schedule. For example, Amanda

When such difficulties occur, it is important to consider the possible reasons. If the young person frequently removes, or attempts to remove, the item representing an activity, this may indicate that he / she is anxious about the activity or dislikes it. This is particularly likely to be the case if the young person then attempts to hide or dispose of the item.

Alternatively, removing the item which represents an activity that appears towards the end of the schedule may arise because the individual has a strong desire to engage in that activity. Removing the item may be intended as a request for that activity.

The young person may frequently rush through activities in the belief that this will result in a preferred activity further down the schedule / timetable taking place sooner.

Difficulties of this nature may result from the schedule covering too many activities. Reducing the number may be appropriate. For example, it may be more appropriate to provide a schedule that covers just a few activities, as is the case with Sarah's schedule; see above.

The "now / next" approach can also be useful. It is employed when Amanda rushes through an activity which precedes one she prefers.

Providing a work system

Bob is provided with a schedule for each lesson. These set out all the tasks he is to carry out in the lesson and provide instructions. In effect, each of these lesson schedules is a work system for the lesson.

Apart from Bob, no other young person featured in the case studies in this guidance material is provided with a work system, although some of them use a finished box.

Amanda has a work system which is set up in her work station before each session. She has 5 trays on her left hand side, numbered 1 - 5 top to bottom. The numbers 1 - 5 are attached with Velcro to a clipboard. Currently, Amanda is still learning how to use the work system: the practitioner physically prompts her to

Amanda then completes the task(s) in the tray independently and places the tray with the completed activities into the empty tray rack on her right hand side which functions as a finished box. The practitioner then prompts her as necessary with the remaining trays.

Providing a finished box

The finished box concept is part of the work system component of TEACCH. A finished box can help the young person to understand that an activity is over and that it is time to move onto the next one. Thus a finished box can help to reduce anxiety and uncertainty.

No young person featured in the case studies in this guidance material actually uses a finished box as part of a work system. However, practitioners supporting some of the young people have adapted the finished box concept, for use in conjunction with the young person's schedule / timetable.

Sarah is one of these young people; the use of her finished box is described and illustrated in the section on her timetable.

Jivan is also provided with a finished box.

Archie uses a finished box in association with his classroom timetable. The flap at the back of the folder he uses for his portable timetable also acts as a finished box.

Cecily places the brailled labels from her timetable on an A4 sized board, which acts, in effect, as a finished box.

Minimising clutter

Minimising clutter is a strategy commonly used in supporting visually impaired young people and sighted autistic young people. It is not surprising, therefore, that it is an important strategy for young people who have both visual impairment and autism. Minimising clutter is a feature of managing the environment which contributes toMinimising clutter may be particularly important when young people are encountering new information or acquiring new skills. As they get older some young people learn for themselves what is important and what should be ignored, and thus cope with at least a degree of clutter. However, minimising clutter and non-essential detail in tactile diagrams, printed worksheets and books remains very important.

Dominic, who has sufficient vision to use visual learning materials, has difficulty if they are cluttered. He has difficulty distinguishing the relevant features of typical worksheets and assimilating the information they contain. He becomes confused if there is too much detail. The following related strategies are therefore employed in work sheets presented to him

Some young people with visual impairment and autism are confused by worksheets which contain several tasks, as they do not know where to start. Such individuals need to have each task presented on a separate worksheet.

Another way to minimise clutter is to use CCTV, as described in the next section.

Providing CCTV

Providing Close Circuit Television (CCTV) may appear to be a strategy designed purely to compensate for the young person's lack of vision. In fact, CCTV may be of considerable benefit to a learner with visual impairment and autism not only because it provides magnification, but because it also minimises clutter.

Cecily uses CCTV very effectively. This is not for reading (she uses braille), but for studying objects and pictures.

Regarding the Long cane as part of the task structure during mobility lessons

Sarah, Sebastian, Tyler and Archie all have mobility sessions during which they are learning to use a long cane. In this context, the long cane can be seen as an aspect of task structure for these young people. This is because it helps to inform the individual at the outset of the session what the focus will be and it is a constant reminder throughout the activity that it is a mobility session.

The long cane can also be viewed as an object of reference for "Mobility training".